Counting Big Cats - a new census of federally regulated big cat populations in the United States

A new peer-reviewed research publication!

I am incredibly excited to announce the publication of my first peer-reviewed research paper in the Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens (JZBG): A Census of Federally Regulated Big Cat Populations within the United States of December 2020. The work was funded by the Feline Conservation Foundation in order to determine the current number of known (regulated) big cats within the country, and conducted independently by yours truly. The journal is open-access, so you can read and download the paper at this link.

There have been previous attempts to conduct a census of big cats in the United States, but they all differed in scope and did not contain the necessary information to be verifiable or replicable. When the FCF approached me about doing a new census, I wanted to be sure that it was done formally and went through a full peer-review process; with all the new interest in captive big cats created by Tiger King (season 2 now confirmed for November) and increased lobbying for the Big Cat Public Safety Act, I wanted it to be able to stand up under any scrutiny. While my census methodology didn’t (and can’t) address the “hot topic” of privately owned, non-regulated big cats, it still contributes relevant data about the distribution of each species and the types of businesses currently holding these animals.

Methodology

In order to conduct a replicable census, I had to work with the only set of consistent and national records that exist: USDA routine inspection inventories for active licensed exhibitors. This means that the census was only able to address what I called “federally regulated” situations. As such, it’s known that there’s some level of error in the data, as the individuals of each species living at non-exhibiting sanctuaries and in private homes were not included. (Because of the unique way federally-run animal facilities are regulated, there were also no USDA inventories available for the National Zoo and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology institute - data for those facilities was acquired through a records request.)

Once all active exhibitors holding big cats had been identified, I researched each facility so I could group them according to reason they maintained a USDA license. Multiple facilities held under the same license were considered individual entities as they were frequently entirely different businesses from each other. I had previously developed a set of definitions of different regulated exhibitor business types for a different research project, and this census utilized a modified version of that set of categories in order to sort the facilities.

In addition, the timing of the census meant that I had to deal with one specific, highly public wrinkle: the big cats held at three of the facilities featured in Tiger King. Tim Stark (Wildlife in Need) Jeff Lowe (Tiger King Park and Greater Wynnewood Exotic Animal Park) had all of their big cats confiscated and rehomed during 2021. Had I conducted the census at any other point in time, these cats would have shown up on USDA inspection reports, either at their respective facilities or at the sanctuaries that they have since been moved to after confiscation. The period in which I was doing data collection, however, coincided with the period after those entities had lost their USDA license (or in the case of Tiger King Park, had yet to apply for one) but before the receiving facilities had had their next routine inspection. Given the popularity of the series and the sheer numbers of cats involved, I knew I couldn’t leave them out of the census entirely. Their numbers are not reflected in the results of the paper - since they were absent from the data - but I added an additional section to the methodology that utilized court documents, media articles, and PR pieces from the receiving sanctuaries to determine how many animals were absent. Those big cats will be counted again in any future census, as they were rehomed to USDA-licensed facilities.

A quick note on taxonomy…

The definition of “big cat” used in this census is a legislative definition, not a phylogenetic one. The public generally thinks of ‘big cats” as including species other than those in Panthera, such as cheetah and puma. When advocacy groups talk about big cats these days, they’re often referring to all larger cats, including clouded leopards, because that’s the group included in proposed legislation. Given the relevancy of this census to current legislative and advocacy topics, I chose to define big cats in accordance with the prohibited wildlife species covered by the Captive Wildlife Safety Act and the proposed Big Cat Public Safety Act.

Big cats in this study therefore are considered to be tigers (Panthera tigris, all subspecies), lions (Panthera leo, all subspecies), cougars (Puma concolor), jaguars (Panthera onca), leopards (Panthera pardus, all subspecies), snow leopards (Panthera uncia), cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus), clouded leopards (Neofelis nebulosa), and any hybrid of those species such as a liger or tigon. (As USDA doesn’t differentiate between ligers, tigons, or any other type of cross in their record-keeping, all of these animals are referred to in the census as lion-tiger hybrids).

And now, the results!

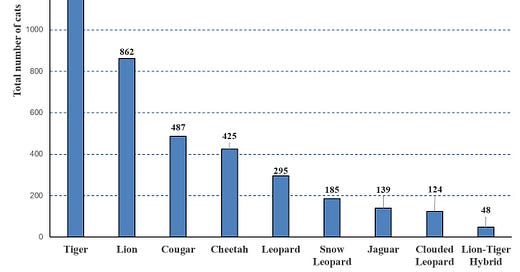

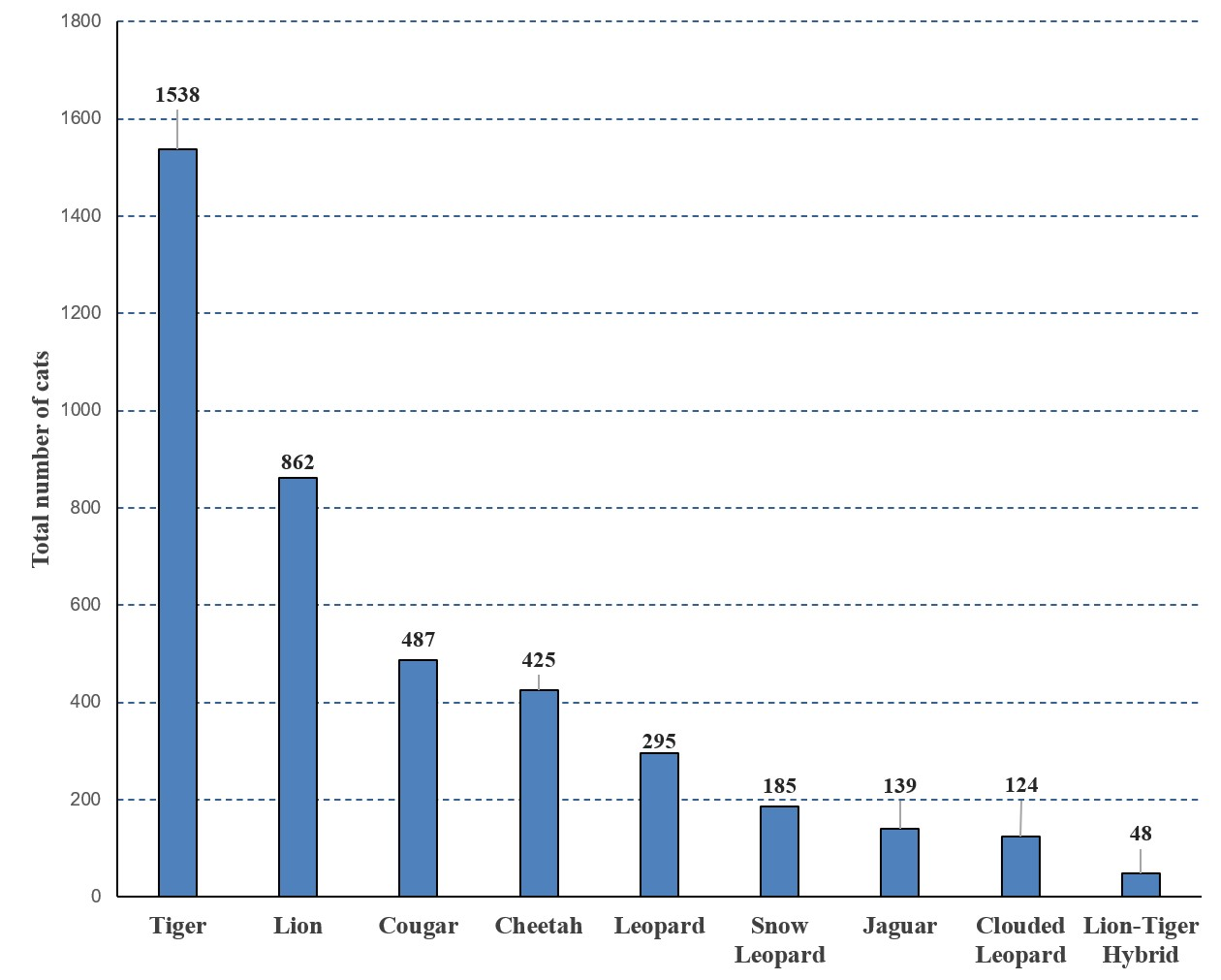

Out of 2226 currently active licensed exhibitors, I found 448 that had any species of big cat in their collection. The census identified a total of 4103 big cats in those facilities. Of those, tigers were the most common, with lions second and cougars third. There were far less of all the other species, with jaguars and clouded leopards coming in last. Only a handful of lion-tiger hybrids were identified in the data. This tracks decently with what we know about the history of big cat species in the United States: tigers and lions have always been the most popular and the easiest to breed, while the other species tended to be less popular, harder to import, and harder to get to reproduce successfully. Some of the less populous species, such as jaguars, now have over half of their populations existing within AZA species survival programs.

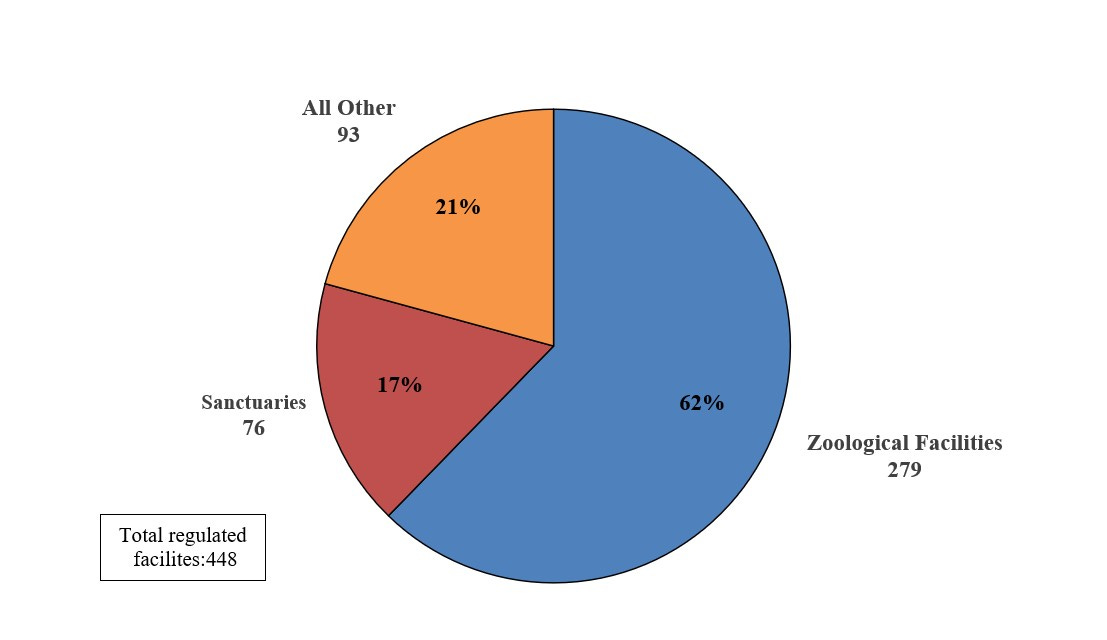

The majority of facilities holding big cats in the United States are zoological facilities, with slightly more of “everything else” (e.g. circuses, education-outreach groups, theme parks) than sanctuaries.

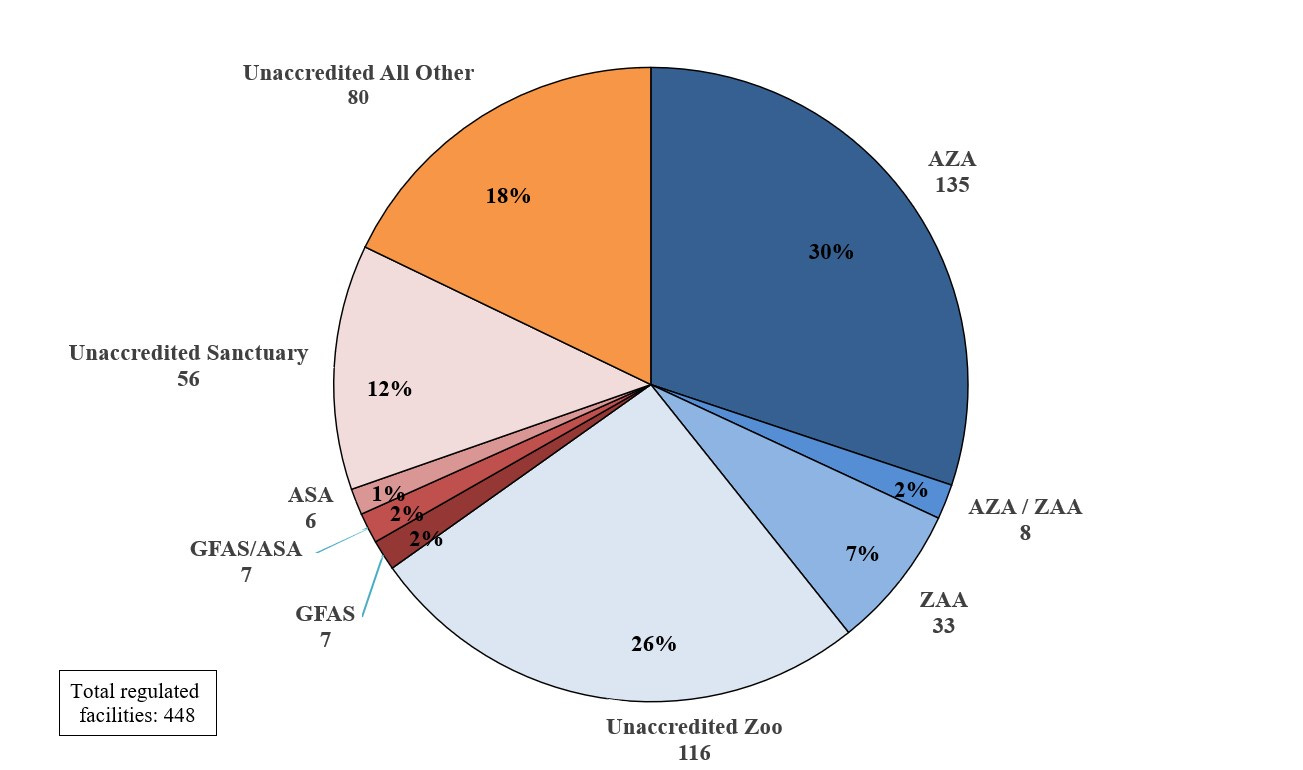

Of those 448 facilities, a third were AZA-accredited facilities (not all of which were zoos), and a quarter were unaccredited zoos. The next largest category was unaccredited non-zoo/non-sanctuary businesses, at one fifth of the total. ZAA-accredited, GFAS-accredited, and ASA-accredited facilities only comprised a small percentage of the total each.

The census results also address the percentage of cats held by accredited facilities, the geographic distribution of the identified exhibitors, and the geographic distribution of each of species. (But I’m going to make you read the paper to find out that part!)

I’m really excited to be finally pinning down some real information regarding the number of big cats in the country. Legislation and advocacy should be based on hard data, not estimates or hearsay, and research like this starts to provide a foundation from which informed efforts can occur.

To everyone who supported this research, thank you so much! It was invaluable. I especially want to thank Dr. Eduardo J. Fernandez, Dr. Kelly Jaakkola, Dr. Jason N. Bruck, and Dr. Melissa Tallman for their support and advice during the publication process.

Excellent! I love good data.