The Big Cat Public Safety Act passed - now what?

HR 263 leaves impacted entities with more questions than answers

Late on Tuesday, December 6th, the news broke that Senator Lankford, the last holdout on the Big Cat Public Safety Act, had changed his mind. With that, HR 263 passed the Senate, and having previously passed the House four months prior, the bill was now on its way to the President’s desk to be signed. A decade after the bill was originally introduced into Congress, the Big Cat Public Safety Act will finally be law.

To the members of the public, that sounds like the end of the story. Private ownership of big cats is now illegal; big cat cubs have been saved from use and abuse by unethical exhibitors. An all-around win for people who care about animals and want to see all captive big cats living in credible, professional, high-welfare situations! Except…

…except that the main thing I’ve heard from acquaintances throughout the zoological industry this week has been “I don’t know how this bill will affect my facility.”

Wow, you might say - after ten years and six different bills, industry professionals haven’t paid enough attention to know how the law will apply to them? Unfortunately, that’s not the problem. While the text of HR 263 is very clear regarding the behaviors its authors wanted to prohibit, a lot of the language surrounding the exemptions for credible entities is vague and non-specific. This has been an issue with multiple iterations of the bill, and is a topic that a number of people - including myself - have brought up repeatedly over the years, with minimal success. In supporting the Big Cat Public Safety Act, the zoological community seems to have assumed that the vague language in the bill will be implemented in a favorable way, but there’s no guarantee of that. The result is that we’ve now got a law restricting certain ways of housing and caring for big cats, and there’s enough room for interpretation in the way it was written that it is unclear the extent to which it will impact the operations of even AZA-accredited facilities. We won’t know for sure how it’s going to shake out - or how zoos might be impacted - until after the Department of the Interior decides how to implement the new law.

A full explainer of the bill, covering definitions, prohibitions, exemptions, penalties, and specific details about my concerns with the language, can be found at this link. This is a breakdown I wrote in 2020 for the previous Congress’s iteration of the bill, then called HR 1380. The name of the bill, therefore, is different in this piece - but the text of the bill discussed is identical to what was just passed into law. If you’re interested in all the gory details, that’s where you should start. In the rest of this post, let’s recap a few of the big topics worth paying attention to as the implementation of the Big Cat Public Safety Act gets underway.

Which set of rules will big cat sanctuaries have to comply with? Most exotic animal sanctuaries are open to the public in some capacity - even if just for very limited tours - and therefore have to be USDA licensed. That means that they fit two of the listed exemption categories in the new law: the “wildlife sanctuary” one and the “USDA Class C” one. The rules required for those two groups, to stay exempt however, are pretty distinct. USDA Class C facilities have to follow specific prohibitions regarding fencing during exhibition, which wildlife sanctuaries don’t; but Class C facilities also have some leeway to allow researchers and other “members of the public” to touch cats in very specific circumstances, whereas the wildlife sanctuary exemption just contains a blanket ban. It seems to have been assumed that sanctuaries would obviously fall under the “wildlife sanctuary” category, but it’s unclear at this point if they’d be able to opt to follow Class C exemption rules instead, or if having an exhibitor’s license at all might automatically force them to be part of that category.

Will there be any backlash against how open-ended the exemption is for state college mascots? The exemption was specifically included to allow the University of North Alabama and Louisiana State University to continue to have live big cat mascots living on their campuses. The stated goal of the bill was to end big cats living in exploitative situations - but with the written exemption imposing no strictures on how they manage their animals, state schools are allowed to own, breed, and even let members of the public have contact with big cats. That’s far looser rules than will now apply to even AZA-accredited zoos! (In an unrealistic but worst-case scenario, the way their exemption is written would literally allow these school to run cub-petting operations, or breed tigers like a puppy-mill, without violating the new law.)

What department will be responsible for the oversight and enforcement of this law? USDA, as part of the Department of Agriculture, is normally the entity that oversees the regulation of exotic animal facilities in the United States - but this bill amends the Lacey Act, which is under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Interior. Does that mean Fish and Wildlife will suddenly have to take on inspecting facilities and keeping track of compliance and complaints, on top of running a registry for privately owned animals? It’s plausible that the Secretary might decide to task enforcement to the USDA on top of their normal remit, but that also creates issues: the department has been perpetually understaffed for the last decade, and the bill does not provide for additional funding to support the increased workload or staffing needs resulting from this law.

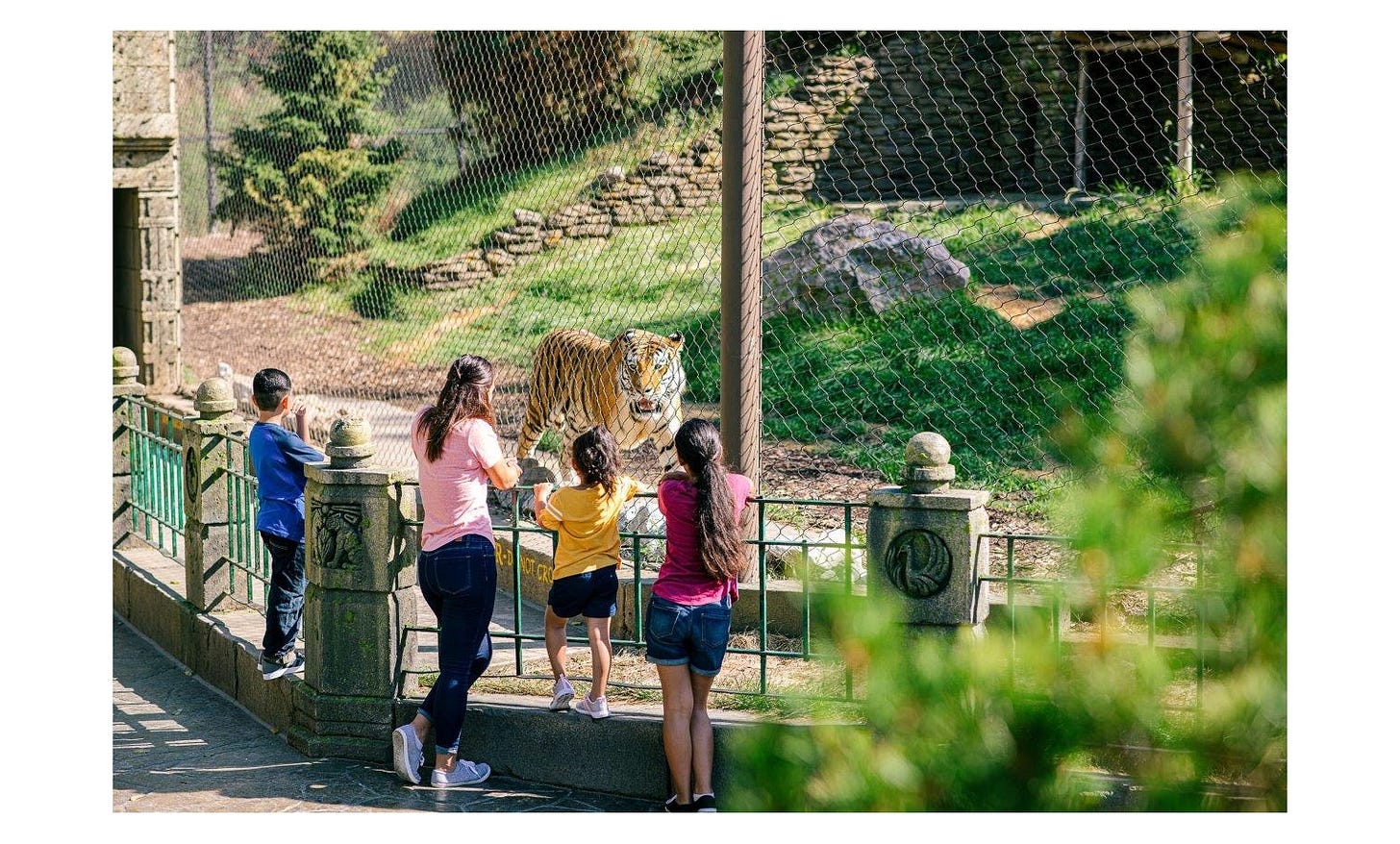

What counts as “a barrier sufficient to prevent public contact”? This is the concern that might have the largest impact on credible zoological facilities if interpreted or implemented badly. The law requires the public to be 15 feet away from most species of big cats at all times unless there’s a barrier that’s “sufficient” to prevent public contact. This term does have some existing meaning within regulation of Class C exhibitors already. The Animal Welfare Act, as promulgated by the USDA, requires that all animals be exhibited with “sufficient barriers between the animal and the general viewing public so as to assure the safety of the animals and the public.” It is unclear if there’s a more detailed definition of “sufficient barriers” anywhere in the standards and regulations. If the USDA is tasked with enforcing the new law, it is likely the same interpretation of “sufficient barriers” will apply; if USFWS (as part of the Department of the Interior) is tasked with enforcing it, there’s no way to know if that department will choose to utilize the same definition as USDA or create their own. If the latter were to occur, and a definition was chosen that was more strict than the one USDA uses, it might have major impact on the ability of even AZA-accredited facilities to maintain an exemption. If “sufficient to prevent public contact” is interpreted to mean “no way it can happen” instead of the USDA’s current “it works if people follow the rules” approach, many existing exhibits at credible facilities - such as the one pictured below - would not be in compliance without renovations or retrofits.

What happens to a facility’s exemption if a violation occurs? It is unclear if entities will just be penalized for violations via the specified fines and jail time, or if they’d also lose their exemption. Obviously the fallout from the latter could be extreme, if zoos or sanctuaries with big cat collections are suddenly in violation of the law for owning / transferring / breeding those animals because they’ve lost their exemption. A badly designed - but probably unlikely - interpretation might require facilities to give up their animals until they could re-qualify for the exemption, or additionally penalize them for maintaining a credible breeding program if cubs were born after an exemption was lost due to an incident.

There’s also a couple interesting issues that have just recently arisen or been brought onto my radar, which I think are worth keeping in mind, but which I haven’t fully researched. They’re pretty surprising. They both have to do with the Class C exemption, which is the bucket that AZA-accredited zoos will fall into. All other zoos will as well, but I’m focusing on AZA here, because this is all about the Species Survival Plans.

Everything I’m about to talk about comes from one part of the Class C exemption - the part that allows for some members of the public to have contact with big cats in very, very specific situations. This would allow for, say, external researchers to come measure the cats while they’re under anesthesia or something. Here’s that language:

‘‘‘(i) does not allow any individual to come into direct physical contact with a prohibited wildlife species, unless that individual is— (…) (III) directly supporting conservation programs of the entity or facility, the contact is not in the course of commercial activity (which may be evidenced by advertisement or promotion of such activity or other relevant evidence), and the contact is incidental to humane husbandry conducted pursuant to a species-specific, publicly available, peer-edited population management and care plan that has been provided to the Secretary with justifications that the plan— ‘‘(aa) reflects established conservation science principles; ‘‘(bb) incorporates genetic and demographic analysis of a multi-institution population of animals covered by the plan; and ‘‘(cc) promotes animal welfare by ensuring that the frequency of breeding is appropriate for the species;”

So what’s the issue? That all sounds good, right? But there’s one industry shift in progress that might really run into an issue here. The text I’ve duplicated for you above explicitly specifies conservation breeding programs. It seems clear that this exemption was originally written to be less restrictive on the function of AZA’s SSP breeding programs, as they’re really the only entity in the US with multi-institution conservation breeding plans for large cats other than cheetah. But… over the last few years, AZA has been redesigning the purpose and function of the SSP programs. The changes are starting to roll out internally now - I’m not sure exactly when they’ll be announced to the public. The major change? SSPs will no longer be about breeding animals for conservation - instead, their new purpose will be breeding sustainable populations of animals for display in AZA zoos1. Does this change mean that AZA SSPs programs will be unable to utilize the leeway in the exemption specifically written for them? Honestly, I have no idea.

Another issue is that the AZA SSPs, as they currently stand - and as I have to assume they will continue to be - are not truly publicly available, as the text of that paragraph also requires. Accessing program documents such as studbooks and breeding and transfer plans requires not only a paid membership to AZA, but an agreement to abide by the organization’s code of ethics and support their mission and goals. In order to get this exemption, AZA may have to actually make all those documents truly public, which would result in a much higher level of external scrutiny of their programs. I believe AZA would be very reticent to do this, but another piece of the test - the part requiring that these plans be submitted to the Secretary of the Interior - might mean they’ll be inherently accessible through a Freedom of Information Act request. I’ve reached out to AZA to learn about their understanding of what it means for these programs to be publicly available, and look forward to hearing back.

A third potential issue - again, caused by this same paragraph(!) - was raised by a business consultant named Nancy Halpern. Writing for the law firm Fox Rothchild LLP, she brought up a concern I hadn’t considered. The text of the law says that the exemption for public contact that’s incidental to a conservation program is only acceptable if it’s not part of “commercial activity.” I have always interpreted that as saying that people couldn’t pay to have the interaction, nor could the zoo market the possibility of the interaction. She pointed out another, much more problematic interpretation of that same language: that zoos using the existence of conservation programs in their own marketing might disqualify them from utilizing that exemption. In her words:

“Theoretically, a volunteer could participate in supporting conservation programs if the facility complied with the requirements to submit the plan (…) but the prohibition of the use of such programs in the course of commercial activity, evidenced, at least in part by “advertisement or promotion of such activity” is problematic. Such programs are often, if not routinely, captured in photographs or videos used to promote the conservation goals of the facility. This is turn, is used for fund raising, often critical for the fiscal well-being of these facilities. Hence, this prohibition, even without considering the impact on “volunteers” but in this provision, any employee not specifically exempted, to assist with these critical conservation programs.”

Halpern’s focus was on the contributions of volunteers working in big cat areas in general, but this issue could also apply to visiting researchers or anyone else who might have a good reason to come into physical contact with the animals. In the end, I think this one comes down to how the Department of the Interior chooses to interpret and enforce the “commercial activity” language. It would be a pretty big problem if this language forces zoos to choose between modifying their current operations and marketing their conservation programs.

In a best-case scenario, the result of all of these issues that have been identified is that nothing much happens. The law is implemented in a favorable way to the industries it touches, and my concerns don’t come to pass. In a worst-case scenario, as you’ve seen, it could get very messy. I’ve always critiqued this bill based on an opinion that legislation that has the potential to impact animal welfare and conservation breeding programs on a broad scale should be as accurate and specific as possible. That didn’t happen with the Big Cat Public Safety Act, so now we just have to wait and see what happens.

All of my citations for the upcoming SSP changes are presentations at AZA annual and mid-year conferences that are not publicly available. There have been regular sessions on the topic at meetings since at least 2019. I’m hoping something will come out publicly about it soon, but I have no idea what that timeline is on.